How Climate Change Threatens Life on the Rockaways

This post explores flooding in the Rockaways as an example of the fragility of human life on America's barrier islands.

On October 29, 2012, Hurricane Sandy washed over New York City’s Rockaway communities with a 14-foot-tall surge of water. The community was devastated. Waves crumpled the beachfront boardwalk like a sheet of paper. Over 1,000 homes were damaged or destroyed. After the water receded, the island’s streets were coated in a thick carpet of sand. Lives were lost, and countless more people were seriously injured.

Life on America’s barrier islands has always been dangerous. Island residents accept this as the cost of living in paradise. Yet as climate change brings more flooding, how much danger is too much?

This is the first post in a series exploring the climate problems facing America’s barrier islands. Each post will examine one set of problems through the experiences of one island. This week, we’ll visit the Rockaways1 to highlight the risks to human life that America’s barrier islands face with climate change.

The Rockaways are perhaps the most highly populated barrier system in America with over 120,000 permanent residents.2 Rockaway beaches attract more than five million annual visitors, mostly day-trippers from the city.

All of these people are increasingly vulnerable to two types of flooding as sea levels rise: storm surge and chronic tidal flooding.

Storm Surge

Storm surge caused the most devastating flooding and loss of life during Hurricane Sandy on the Rockaways. Here’s how it works: the ocean swells higher than the high tide line—sometimes 10 to 20 feet higher—and forces a wall of water onto the shore. If the topography of the shore is low enough, the surge washes over the island and into the bay carrying with it trees, cars, and buildings.

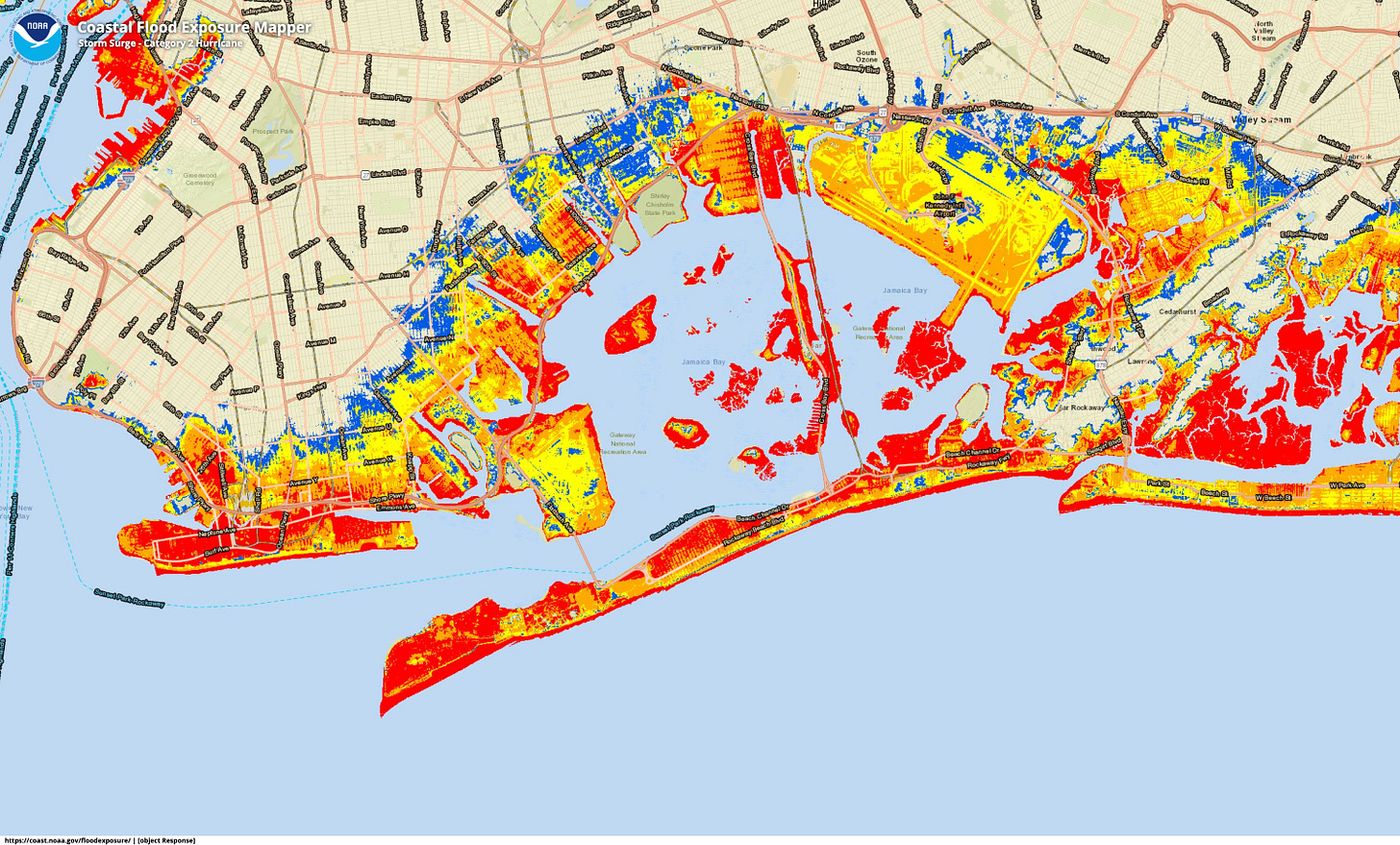

Flooding from Sandy was already devastating. Climate change will make storm surges more dangerous and more frequent. Hurricane Sandy made landfall just below the threshold for a Category 1 hurricane. If a Category 2 hurricane reaches the Rockaways in the future, the island could be fully flooded, in some places over nine feet above ground.

At least 10 people died on the Rockaways during Sandy. While every loss of life is significant and should be avoided, this is a relatively small number of deaths compared to the scope of the storm’s property damage. This suggests that the island has an extensive evacuation system in place to move people out of harm’s way. The greatest potential loss of life from future storms will be with low-income and elderly populations on the island and coastal communities behind the island.

Low-income residents, especially elderly low-income residents, are the most challenging to evacuate. Many low-income residents cannot afford transportation to leave the island or to pay for temporary housing. Public storm shelters can be crowded and uncomfortable, leading many residents to shelter in place. If they stay, they are highly vulnerable to storm surge, and they put first responders at risk when they need lifesaving support. FEMA recently increased its financial support for evacuees, but it’s not yet clear how effective this program will be.

During Sandy, many people expressed “a New York-style nonchalance” and decided to shelter in place. This sentiment is far too common among barrier island residents. “The last storm wasn’t bad; I’ll be fine.” However, a post from the Rockaway Times describes the gruesome details of what can happen to people who stay: they drown in their basements, fall down stairs in the dark, or are physically unable to escape to higher ground.

Beyond the island, people living behind the Rockaways are also vulnerable to storm surges. Today over 250,000 people live along the shores of Jamaica Bay; that’s close to the population of Newark, New Jersey. Barrier islands provide natural friction against storm surges, reducing the force of waves hitting coastal communities. However, the islands provide little protection against the most severe storms.

Further, critical lifesaving facilities are in the floodplain behind Jamaica Bay, including hospitals, fire stations, and police stations. Flooding at these facilities would severely hamper NYC’s emergency response capacity. Plus, JFK Airport—one of the highest-traffic airports in the world—sits on the edge of Jamaica Bay and is highly susceptible to storm surges. If the airport is flooded during a storm, emergency response crews may be unable to land for days following the storm.

Chronic Tidal Flooding

Carried by wind and the gravitational pull of the moon, ocean tides swell and quickly flood low-lying coastal communities, even on sunny days. This is called tidal flooding. Today, tidal flooding is not too deep—maybe one or two feet. But a couple of feet of flooding is enough to submerge streets and flood basements for hours. Over time, these floods will rise higher, gradually flooding more coastal communities. By 2100, many coastal communities will see monthly, if not daily, tidal flooding.

While tidal flooding does not have the dramatic force of a storm surge, it can lead to chronic and widespread health issues. Building materials that are regularly flooded can, if left untreated, develop mold and expose residents to respiratory diseases. Flood waters can pick up and distribute pollutants. Low-lying electrical equipment can malfunction, causing fires and electric shocks. And flood waters can cut residents off from essential services like hospitals.

The Rockaways are highly susceptible to chronic tidal flooding. Based on current projections, the Rockaways can expect to see at least six feet of flooding above the current tide level every year. Like most barrier islands, the flooding would primarily come from Jamaica Bay and would cover most of the island. Only the beachfront dunes would be spared. Climate Central estimates that almost 65,000 people—half of the Rockaways’ population—live in the future tidal floodplain.

The good news is that tidal flooding is predictable. Infrastructure projects—like raising streets and improving drainage systems—can make it easier for communities to live with water. But this infrastructure will be expensive to build. Can we afford to continuously raise every barrier island with climate change?

Life After Sandy

The Rockaways have largely recovered and fortified in the past 12 years since the storm. The city rebuilt the boardwalk—this time with concrete and a deep dune system to protect it. Residents rebuilt their homes higher and stronger. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers recently completed a beach stabilization project. And NYC added a new ferry stop to the island, which draws more visitors and supports an emerging food, drink, and hotel scene.

Unfortunately, today’s Rockaway renaissance may just be the calm before the next storm. Even with these fortifications, Rockaway residents, and the hundreds of thousands of people living on the shores of Jamaica Bay, remain vulnerable to deadly flooding from climate change. With storms like Sandy becoming more frequent, the Rockaways will likely have less time to recover between storms; perhaps just a few years.

How long we can sustain life as we know it on the Rockaways and other American barrier islands?

I’ll leave you with a surprisingly catchy song by Ladyaanty, a Rockaways resident during Sandy, about the resilience of her community as they navigated the storm and its aftermath:

More on America’s Barrier Islands

This post is part of Gumption’s plan for America’s barrier islands. It’s the first in a series exploring the climate problems facing barrier islands. Subscribe today to follow the plan.

Your Turn!

Do you think life on America’s barrier islands is sustainable? Share your thoughts in the comments below or email me at blake@gumption.earth!

The “Rockaways” refers to the Rockaway Peninsula, NY. While it’s not technically an island today, there’s evidence it was an island recently and it’s shaped by the same geomorphic forces of true barrier islands. For this plan, I consider Rockaway Peninsula to be a barrier island.

NYC Population FactFinder, ACS 2017 - 2021. NTAs include Far Rockaway-Bayswater [QN1401], Rockaway Beach-Arverne-Edgemere [QN1402], Breezy Point-Belle Harbor-Rockaway Park-Broad Channel [QN1403], and Jacob Riis Park-Fort Tilden-Breezy Point Tip [QN8492].